The wise words of my grandmother

My grandmother often used to say, “I know that I know nothing.” Even as a child, I thought about this sentence. It seemed to me somehow unnecessary because it was obvious. So I paid attention to when my grandmother said it to find out why she used it. Because she was a very clever and refined woman who was held in high esteem and she knew how to subtly influence others.

She used this phrase deliberately

I noticed that she used the phrase for example when she was talking to highly educated people and they were trying to explain complicated things to her. By claiming not to know anything, she encouraged her counterpart to go into the topic of conversation in greater depth. Furthermore, as a non-knowledgeable person, she placed herself hierarchically below the speaker and thus expressed respect for him and his (possible) knowledge. This flattered the speaker, of course, and created a relaxed atmosphere for the conversation. Ingeniously, however, my grandmother did not say: “I don’t know anything about that” but “I KNOW that I don’t know anything”.

Because it comes from Plato one has respect

As a child, this impressed me very much. It was only much later that I found out that the sentence came from Plato. So if the person my grandmother was talking to was actually reasonably educated, this sentence naturally made him sit up and take notice, because it implied that my grandmother not only had Cicero, Socrates and Plato on her bookshelf, but actually engaged in this reading. Despite professing ignorance, this elevated her to eye level with the speaker and earned her (even more) respect. Two intellectuals among themselves, so to speak.

No one notices the comedy behind it

Actually, I wouldn’t call my grandmother an intellectual, but she was very well read on certain subjects and had acquired an enormous wealth of knowledge over the many years (she died at 96). This gives Plato’s saying a certain comical quality in my eyes or ears. However, no one seems to have noticed it except me, not even my grandmother, or especially not my grandmother. If she had, she might never have used the phrase again. For I do not believe that it was her intention to appear comical.

The effect of the apparently profound

But back to the imaginary conversation. Of course, there were interlocutors who did NOT know the origin of the phrase. But it still worked brilliantly because it had the same effect as it did on me as a child. It sounded to me at the time as if there was some deep meaning behind it, but somehow you couldn’t quite grasp it.

Comparison with the Japanese koan

Today I am thinking of a Japanese koan such as, “What do you hear when you clap one hand?” The obvious absurdity of this sentence is supposed to cause thinking to fade away when meditating. The logic or illogic of the statement is intangible. And when the words are repeated in the mind over a long period of time, this causes the thinking to go round in circles and eventually fade away altogether. A technique that can be found in this or similar ways all over the world and is ultimately intended to bring one a little closer to enlightenment or even to attain it. Because if a room (the head) is stuffed to the top with all kinds of rubbish (the thoughts), then of course no light can get in. Goodbye enlightenment. I didn’t know anything about that at the time, but somehow, even without thinking, that is, purely intuitively and emotionally, you can feel this spiritual approach. At least that’s how I felt. And I think my grandmother’s counterpart did too.

The origin of the words is not mentioned

Interestingly enough, my grandmother gave everyone the feeling that there was a great deal of knowledge behind her words precisely by professing to know nothing. Which, in a way, was true. Incidentally, I did not observe her ever explaining the origin of the words. Also a clever move. This gives the conversation with those who have read Plato a certain conspiracy character and those who do not know him do not feel exposed.

As a child I experimented with the phrase

Since there was no Internet back then and I couldn’t ask Uncle Google and Auntie Wiki about the connections, my curious nature later led me to conduct experiments with this sentence myself. It didn’t work on adults, I realised immediately. Most of them knew my grandmother and of course knew that I had picked up the phrase from her. And the others somehow heard that I was parroting empty phrases that made no sense to me. Besides, they assumed that I hadn’t read Plato at that age. (Why, actually?) Among my peers, the saying was ignored or acknowledged with rolling eyes directed towards heaven. In any case, I did not receive the hoped-for respect that my grandmother usually earned with these words.

Emphasis changes the meaning

Nevertheless, the whole thing didn’t leave me alone. Even today, as you can see. And because I was (and still am) a play rat and the sentence also has a certain musicality, I began to play around with it rhythmically. I found that the stress on the words can make a huge difference. For example, if I say: “I know that I don’t know anything”, it sounds to me as if it continues with: “And YOU don’t know. Aaagh. And that’s the way it should stay.” If, on the other hand, I emphasise: “I KNOW that I don’t know anything”, then that might mean: “Well, at least I KNOW. So I could change something” Or it means: “Yes, yes, I KNOW. Leave me alone with it!” If I say, “I know that I don’t know anything,” it may mean that there are others who do know. With the emphasis “I know that I know NOTHING, I can’t help thinking that there is soooo much knowledge in the world that these few thoughts in my little head are as ridiculously little as a few grains of sand on the beach.

My emphasis favourite

Even then, I picked my favourite out of all these variations of emphasis. Namely: ” I know that I KNOW nothing” This statement gives my thinking and my imagination absolute freedom. Everything is possible. Maybe I am a brain in a petri dish and my whole life takes place only imaginary in my grey cells. I do not know. Maybe I don’t exist at all, or maybe I exist in a completely different way than I imagine. I do not know. But maybe there is a physical life after all and I am Anni Lenz, the yodeller, flesh and blood. I don’t know. This theme is taken up in many films. In “Matrix”, for example, and also in “Avatar”. Personally, the great ignorance doesn’t frighten me. On the contrary. It inspires not only the imagination but also action. Thinking-feeling-doing. Everything is possible. You have the choice. (or?)

Knowledge and truth in times of pandemic

For as long as I can remember, I have felt these innumerable possibilities and the infinite freedom that comes with them (because it really is more of a feeling than a thought construct) and I tend to be cautious if not sceptical about the concepts of knowledge and truth. I tend to question everything. Most of the time, I consider the opposite of a statement to be at least as possible as the statement itself. Especially when there is talk of established facts. This attitude of mine has been reinforced by the time of the pandemic, when so-called “established facts” seem to have turned into the opposite within a very short time and are still doing so. But that is another topic…..

Accumulate knowledge by learning

Nevertheless, I acquire so-called knowledge with great zeal. I love learning for my life. I don’t know why, but I enjoy it. In the meantime, I can play a lot of musical instruments more or less well and speak at least some of the languages. And a lot of “knowledge” about plants and animals and the connections in nature has accumulated in my head.

Knowledge can also be a hindrance

This “knowledge” – I deliberately write it in inverted commas – can definitely get in my way. Here is an example:

I am (among other things) a goldsmith. After having worked in this beautiful profession for several years, many years ago I wanted to deepen my knowledge and skills and had started to study fine arts, of course first in the offered jewellery and small sculpture class. One day I had designed a necklace that was to have a special clasp, something new, my own invention, so to speak. But since I had learnt in my previous basic training, i.e. in my solid goldsmith apprenticeship, how to make chain clasps in the most different ways, these learned techniques could be called up in my head, but they stood in the way of my creativity to such an extent that I could not manage to approach my task freely. I kept coming back to the old forms stored in my head and could not break away from them. It was like a rigid template. In fact, I left the jewellery class at that time for these reasons and turned to painting.

Critical approach to questionable knowledge

My personal approach to knowledge is ambivalent. Yes, knowledge sets you free. But not always. And yes, knowledge is power. And therefore also entails responsibility. But above all, knowledge is questionable, open to doubt and should be treated with caution. Where does knowledge come from? Who has an interest in my believing in something? And why? Is there only one truth? Is there one at all? These questions are more present than ever before. It is worthwhile to pursue them. My grandmother, or Plato, started this avalanche of existential questions with a short sentence:

“I know that I know nothing”

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

A subsequent remark

Now that it has been pointed out to me for the second time that the sentence does not come from Plato but from Socrates, I would like to say something about it:

Socrates himself left nothing in writing. What we think we know about him was written down by his students. Plato wrote most of it. It is possible that Socrates actually said: “I know that I know nothing”. But maybe Plato just put it in his mouth because he thought it was appropriate. Who knows? That’s why I feel the sentence belongs to Plato. I hope no one takes offence at this little liberty.

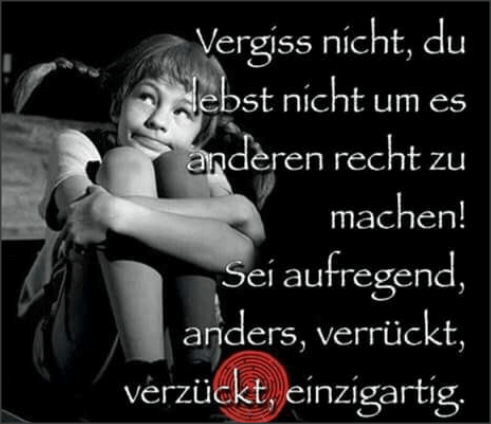

Funnily enough, however, I clearly assign some of my favourite quotes to Pippi Longstocking and would never think of writing Astrid Lindgren underneath (although some people do). However, that is something different. Pippi, unlike Socrates, is a fictional character. Everyone probably knows that her stories are written by Astrid Lindgren and not Plato.

(“Remember: You don’t live to please others.

Be exciting, be different, be crazy, be wildly unique”)

I think it shouldn’t matter whether you write the name of the author or the character under a quotation, because actually they can’t be separated.

You like my blog and would like to support me?